A team of researchers at the Harvard Wyss Institute have developed a soft, hydrogel scaffold that can function as a living electrode for brain-computer interface applications. The researchers used electrically conductive materials and created a porous and flexible scaffold using a freeze-drying process. They then seeded the scaffold with human neural progenitor cells (NPCs) and cultured the scaffolds for extended periods, prompting the cells to differentiate into a variety of neurons and astrocytes. The researchers hope that the resulting ‘living electrode’ could be useful for braincomputer interfaces, as its soft and flexible nature will help it to conform with soft neural tissues and its cellular cargo will help to enhance its biocompatibility and potential efficacy.

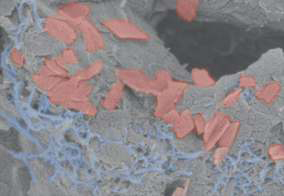

The scaffold consists of a soft hydrogel (gray) that contains carbon nanotubes (blue) and graphene flakes (red) as conductive materials to transmit electrical impulses throughout the scaffold. Credit: Wyss Institute at Harvard University

Brain-computer interfaces hold enormous promise in unlocking therapeutic outcomes that would have seemed like science fiction just a few short years ago. From controlling wheelchairs with the mind to restoring sight to the blind, the opportunities in enhancing patient well-being are huge. However, the technology still has a way to go and on a rst look, machines and the human body are not a match made in heaven. The interfacing electrodes in such systems are typically made using metal and are rigid, both of which do not assist the technology in non-invasively interacting with delicate neural tissues.

These researchers set out to create an electrode that is not just flexible, but also covered in living neural cells, and is based on the concept that living tissue is likely to be the most biocompatible material to interface with other living tissue. The researchers also conceived the cell-laden material as delivering electrical impulses more naturally through cell-cell contact.

“This conductive, hydrogel-based scaffold has great potential,” said Christina Tringides, a researcher involved in the study. “Not only can it be used to study the formation of human neural networks in vitro, it could also enable the creation of implantable biohybrid BCIs that more seamlessly integrate with a patient’s brain tissue, improving their performance and decreasing risk of injury.”

To create their scaffolds, the researchers used an alginate hydrogel and added some carbon nano-materials for electrical conductivity before a final freeze-drying step. The freeze drying process creates ice-crystals in the material that then sublime during freeze-drying, leaving many pores into which cells can enter and live. They seeded the scaffolds with neural progenitor cells, which then differentiated into more mature neural cells during an extended culture period.

“The successful differentiation of human NPCs into multiple types of brain cells within our scaffolds is confirmation that the conductive hydrogel provides them the right kind of environment in which to grow in vitro,” said Dave Mooney, another researcher involved in the study. “It was especially exciting to see myelination on the neurons’ axons, as that has been an ongoing challenge to replicate in living models of the brain.”

Researchers at the National Eye Institute, which is part of the National Institutes of Health, have created a method to 3D bioprint eye tissue that forms the outer blood-retina barrier. This tissue supports the photoreceptors in the retina and is implicated in the initiation of agerelated macular degeneration.