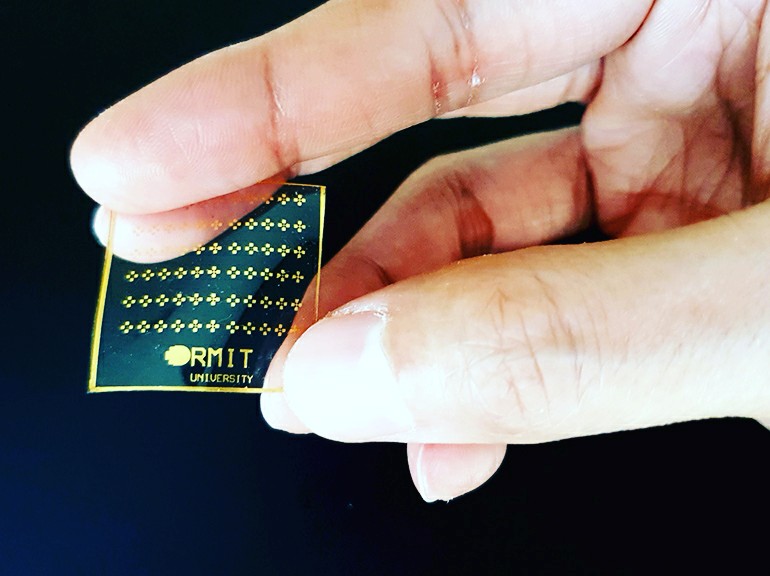

Scientists at the RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia have announced the development of an artificial skin material that can sense pain, temperature, and pressure. It’s remarkable because it replicates how real skin responds to stimuli, which sends appropriate electric signals through neural pathways to the brain. The technology is slated to allow for life-like transmission of tactile sensations through prosthetic arms and legs, and may even help replace skin grafts with artificial solutions.

According to RMIT, the electronic skin ‘replicates’ how our native skin detects pain, sending out signals just as fast as healthy nerves. According to Madhu Bhaskaran, a corresponding author of a study describing the technology in journal Advanced Intelligent Systems, “We’re sensing things all the time through the skin but our pain response only kicks in at a certain point, like when we touch something too hot or too sharp. No electronic technologies have been able to realistically mimic that very human feeling of pain – until now. Our artificial skin reacts instantly when pressure, heat or cold reach a painful threshold.”

The researchers made three separate devices, including one that senses pressure, one temperature, and one pain, though it should be possible to combine them into one. This required a new approach to stretchable electronics, using oxide materials combined with silicone to make something that can be bent and flexed and not break. A special temperature sensitive coating was developed that can quickly transform itself, something that is immediately measurable using electronics. The last necessary component was brain-like memory cells that are used to decide how to process the sensory data and send the right signals when limits are reached.

“We’ve essentially created the first electronic somatosensors – replicating the key features of the body’s complex system of neurons, neural pathways and receptors that drive our perception of sensory stimuli,” said Md. Ataur Rahman, one of the study co-authors. “While some existing technologies have used electrical signals to mimic different levels of pain, these new devices can react to real mechanical pressure, temperature and pain, and deliver the right electronic response. It means our artificial skin knows the difference between gently touching a pin with your finger and accidentally stabbing yourself with it – a critical distinction that has never been achieved before electronically.”